Angels Camp

Located about ten miles south of the county seat at San Andreas, Angels Camp was one of the earliest important mining communities along the Mother Lode region of California. Situated in southwestern Calaveras County, on State Routes 49 and 4, it lies at the confluence of Angels Creek, China Gulch, and Dry Creek. Angels Creek has its headwaters about four miles above Murphys and is fed by Sixmile, Indian, and Dry creeks before flowing into the Stanislaus River near Vonich Gulch, now beneath the waters of New Melones Reservoir, created by the construction of New Melones Dam in 1979 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, to replace the original 1926 dam.

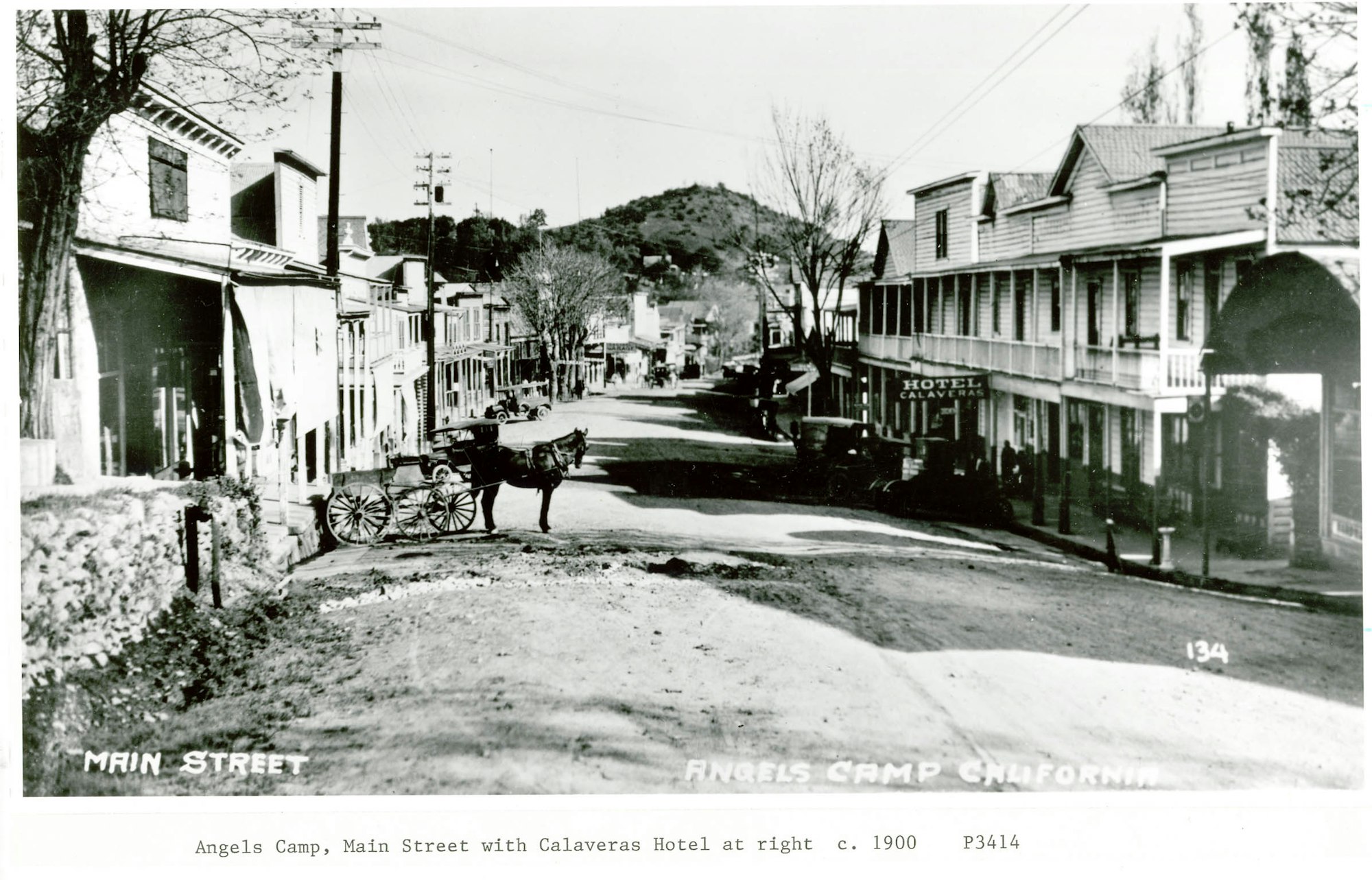

The area was first occupied by Native Americans, then traversed by explorers and trappers, settled by Euro-American placer miners during the Gold Rush, later became a commercial and trading center, expanded during the 1880s-early 1900s hard rock mining boom, slumbered during the World War I era, boomed again with the reopening of the hard rock mines in the 1930s, only to be shut down again in World War II.

Mining and Settlement

The history of Angels Camp and Altaville is like that of many other such Gold Rush Era communities in the California foothills, with their booms and busts, colorful characters, and almost century-long dependence on mining. Located in the Angels Camp Mining District, which consists of that portion of the Mother Lode between the San Andreas district to the north and the Carson Hill district to the southeast, it is both a lode and placer district, though the lode mines have been more productive. By 1885 Angels Camp was one of the major gold-mining districts in California. All of the major mines were shut down during World War I, but there was some activity again during the 1930s, with an estimated total output of at least $30 million, but probably considerably more (Clark 1970:25). The industry experienced several significant revivals, particularly in the late nineteenth century and again in the early twentieth, and provided the lifeblood of the Angels Camp area.

The prosperity of the communities was first based upon the rich placer gold found in Angels Creek and its tributaries of China Gulch, Six Mile Creek, Cherokee Creek, Greenhorn Creek, and their drainages. It wasn’t long, however, before both communities had become trading centers for the neighboring mines. Altaville, first known as Forks-in-the Road and Cherokee Diggings, took its present name at a town meeting in 1857 (Gudde 1969:8), while Angels Camp was named for Henry and George Angel, who set up a trading post there in the winter of 1848.

Rhode Islanders Henry and George Angel, prospectors from Stevenson’s California regiment, were members of James H. Carson and John W. Robinson’s mining expedition of 92 men who departed from Monterey on 4 May 1848, to prospect in the mining regions. Part of Company A, Third Regiment, U.S. Artillery, by August of 1848 they were at Weber’s Creek, then traveled south with Carson until reaching the Stanislaus watershed. Prospecting first at Carson’s Creek, where they took out a large amount of gold, in December of 1848 they returned to Angels Creek and established a store at its intersection with Dry Creek and the creek now named for them. There they prospected and set up a primitive trading post to exchange native goods for gold.

Whether they worked for themselves or Captain Weber, the founder of Stockton, is not clear, but Weber set up trading stores for the Murphy brothers and Dr. Isabel, so he might also have funded the Angels (Carson 1991:9, Limbaugh and Fuller 2004:16-17). They were certainly in operation by December of 1848, as in the middle of that month four miners, on a trip from Mokelumne Hill to the Stanislaus Diggings, noted... “After two days travel we reached Angel’s called after a trader of that name who had a store in the camp at the time and whose log cabin was situated pretty near the spot where Scribner’s store now stands. There were some hundred or so miners in the vicinity, most of whom were doing well” (San Andreas Independent, July 17, 1858).

By the spring of 1849 the camp had a population of over 300 (Wood 1955:9) when James H. Carson described it upon his return after his discovery of gold at Carson’s Creek the previous year:

We continued on to the old diggings from Stockton. When we reached the top of the mountains overlooking Carson’s and Angel’s creeks we had to stand and gaze in silence on the scene before us—the hill-sides were dotted with tents, and the creeks filled with human beings to such a degree that it seemed [as] if a day’s work of the mass would not leave a stone unturned in them (Carson 1991:19).

Shortly thereafter Angel sold his business to J.C. Scribner, who erected a frame, and later, a stone building on the location (Elliott 1885:69). In 1853 Angel opened Magee and Angel’s Hotel in a partnership in Cave City. By 1857 Henry and George were running a pack train into the mountains to supply the distant miners, and at some point George disappeared. Henry, however, returned to the pursuit of mining, working as a miner in Copperopolis in 1867 and as a partner in a gravel mine near Calaveritas in 1879, where he was later listed as an Election Inspector in the district. For the last 30 years of his life he lived in the vicinity of Fourth Crossing where he mined in partnership with Henry O’Dell. He died broke, having sold all of his possessions to defray the expenses of O’Dell’s burial. He succumbed to heart failure, at the County Hospital in San Andreas on March 17, 1897, aged 72, and was buried in the Peoples Cemetery in San Andreas; no tombstone marks his grave.

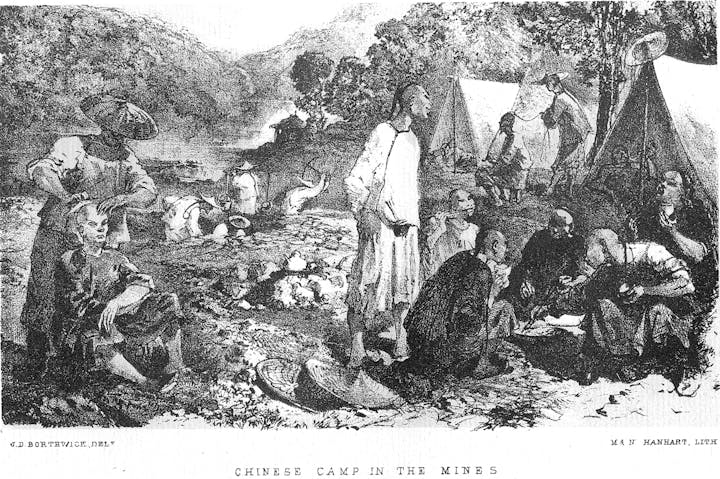

For the most colorful descriptions of Angels Camp in the early 1850s we are indebted to J.D. Borthwick, an artist who spent three years in the mines from 1851-1854:

While walking around the diggings in the afternoon, I came upon a Chinese camp in a gulch near the village [either China Gulch or Angels Creek]. About a hundred Chinamen had here pitched their tents on a rocky eminence by the side of their diggings. When I passed they were at dinner or supper, and had all the curious little pots and pans and other “fixins” which I had seen in every Chinese camp, and were eating the same dubious-looking articles which excite in the mind of an outside barbarian a certain degree of curiosity to know what they are composed of but not the slightest desire to gratify it by the sense of taste. I was very hospitably asked to partake of the good things, which I declined; but as I would not eat, they insisted on my drinking, and poured me out a pannikin full of brandy, which they seemed rather surprised I did not empty. They also gave me some of the cigaritas, the tobacco of which is aromatic, and very pleasant to smoke, though wrapped up in too much paper.

The Chinese invariably treated in the same hospitable manner any one who visited their camps, and seemed rather pleased than otherwise at the interest and curiosity excited by their domestic arrangements (Borthwick 1948:261).

Borthwick went on to describe a ball that occurred at C.G. Lake’s Hotel that night:

In the evening, a ball took place at the hotel I was staying at, where, though none of the fair sex were present, dancing was kept up with great spirit for several hours. For music the company were indebted to two amateurs, one of whom played the fiddle and the other the flute….

It was a strange site to see a party of long-bearded men, in heavy boots and flannel shirts, going through all the steps and figures of the dance with so much spirit, and often with a great deal of grace, hearty enjoyment depicted on their dried-up sunburned faces, and revolvers and bowie-knives glancing in their belts; while a crowd of the same rough-looking customers stood around, cheering them on to greater efforts, and occasionally dancing a step or two quietly on their own account. Dancing parties such as these were very common, especially in small camps where there was no such general resort as the gambling-saloons of the larger towns….The absence of the ladies was a difficulty which was very easily overcome, by a simple arrangement whereby it was understood that every gentleman who had a patch on a certain part of his inexpressibles should be considered a lady for the time being. These patches were rather fashionable, and were usually large squares of canvass, showing brightly on a dark ground, so that the “ladies” of the party were as conspicuous as if they had been surrounded by the usual quantity of muslin (Borthwick 1948:261-263).

Gambling, too, was a popular entertainment in Angels Camp, as it was throughout the mines. As noted in a Gold Rush diary:

Gambling and Gamblers filled the Camps, every Tent and Grocery had a Monte Table in it where Most of the Miners spent their Nights and lost their Gold Dust….Gambling and Gambling houses were the order of the day and Monte the favorite Game, every evening found the saloons full, [with] New diggings discovered with the Miners to dig the gold, went the Gamblers to fleece them out of it, some ludicrous scenes occurring day & night in these saloons…I often called attention to the difference in attire between Miners and Gamblers who were usually neatly and well-dressed; in these dens thousands of dollars would change hands daily, sometimes a miner would make a run on a Game and break it in a few hours, but this was seldom the case (Leonard W. Noyes, Murphys 1851.

In April 1854, the German novelist and traveler Fredrich Gerstacker visited Angels Camp to gather material for a book, and later described the town:

It seemed to be or to have been a very important gold field. A number of tents were pitched between the hills and the soil of the broad bed of the river was everywhere turned up and the lights shining down from the hills afforded proof of the crowds of diggers who were trying their fortunes here (in Buckbee 2005:186).

Hard Rock Mining, The Second Gold Rush

Lode mining began in the 1850s along the Mother Lode vein which coursed northwest-southeast just through Angels Camp. In 1854, the first important quartz locations were made, all on the Davis-Winters Lode, where the Winter Brothers (Edmund and Augustus) and Davis & Co. were ground-sluicing. This broad vein or lode (10 to 90 feet wide) roughly paralleled present Highway 49, running southeasterly from Altaville down to Angels Creek. Over the next few years the vein was developed all the way to the creek by utilizing small open pits or shallow shafts and milling in mule or horse-powered arrastras, as well as water powered mills with overshot wheels. Some mills, located above the water ditch, were powered by steam, but with light stamps and low tonnage. In 1858 four steam mills and nine water mills were operating.

By 1857 Angels Camp was a bustle of mining activity:

There are several mills now in operation, and others in course of erection. – On entering the place one is reminded of a lively manufacturing place, and attracted by the steam and smoke pipes in every direction. A new mill has recently been erected by Wentworth, Benjamin and others, and is one of the best constructed mills in the state, containing many of the recent improvements. The lodes of Angel’s are of a rich, ouphurate character, and the proprietors are full of enthusiasm, having great confidence in their richness (in Long 1976:4).

The same writer went on to mention several other mills and claims working in the area, including the Winter Brothers, Dr. Hill, Major Fritz, and Lightner & Cameron. Five mills were depicted on a lithograph of Angels Camp produced that same year: Lightner, Winter Brothers, Maltman, and Dr. Hill, and others (Kuchel & Dresel 1857).

Bayard Taylor, who traveled through Angels Camp in 1859, described the mining activity:

In the neighborhood of Angel’s, I noticed a number of mills, many of them running from twenty to thirty stamps. Some of these mills are said to be doing a very profitable business. They have effectually stripped the near hills of their former forests, to supply fuel for the steam-engines and beds for the sluices in which the gold is separated from the crushed rock. The bottoms of the sluices are formed of segments a foot thick, sawed off the trunks of pine-trees and laid side by side; yet such is the wear and tear of the particles of rock and earth, carried over them by the water, that they must be renewed every two or three weeks (Taylor 1951:110).

There was intermittent mining activity through the 1860s, and another small boom in the 1870s, but not much appreciable activity. Mining, however, continued to provide the major tax base for Angels Camp. In 1860-61, the township raised $1,270, or 12.1 percent, of its total revenue by assessing stamp mills, arrastras, machine shops, water wheels, ditches, and other types of mining equipment. Assuming mining families were representative of the general population, their related taxes in conjunction with the mines provided 62 percent of the revenue base of the township (Limbaugh and Fuller 2004:313).

By the end of the Civil War it was estimated that some 20 to 50 thousand ounces of gold had been recovered from the Winter Brothers claim, but the low grade of the ore, coupled with the difficulty of processing the sulphurets bound up in it, ended the boom. Of the dozens of claims that were filed in the 1850s, only 11 ultimately proved productive, and most were consolidated by secondary or tertiary developers. Eventually, nearly all of the major claims at Angels Camp were brought into the corporate structure of four companies: the Sultana, Angels, Lightner, and Utica (Limbaugh and Fuller 2004:57-58, 60).

After two decades of steady growth, the post Civil War era of the 1870s saw a period of consolidation, retrenchment, and economic decline. Copper mining had ended, drift mining was falling off, few lode mines were operating, and the population of the mining camps, including Angels Camp, dwindled.

It was another two decades before mining picked up again with the advent of the hard rock mining boom of the late 1880s, which continued until most of the mills were shut down for World War I. At this time, a combination of advanced mining and milling technologies, primarily the invention of dynamite and the development of square-set timbering in the Comstock lode, the chlorination process, water or steam power drills, water pumps and air-power, along with investment of foreign capital, provided for the resurgence of the mining industry in Calaveras County and the foothills.

Beginning about this time (1888) and continuing for several decades, great improvements were made in mining and milling methods. These changes enabled many more lode deposits, especially large but low-grade accumulations, to be profitably worked. The improvement of air drills, explosives, and pumps, and the introduction of electric power lowered mining costs greatly. The introduction of rock crushers, increase in size of stamp mills, and new concentrating devices, such as vanners, lowered milling costs. Cyanidation was introduced in 1896 and soon replaced the chlorination process (Clark 1970:7).

This “Second Gold Rush” occurred around Angels Camp from the late 1880s to the advent of World War I, with around 320 stamps dropping, led by Charles D. Lane’s Utica Mine. It was at this time that the deep mines were developed and consolidated. Among the most productive lode mines in the Angels Camp District were the Angels ($3.25 million+), Angels Deep ($100,000+), Gold Cliff ($2,834,000+), Lightner ($3 million+), Madison ($1 million+), Mother Lode Central ($100,000+), Sultana ($200,000+), and the Utica ($17 million+). The total production for the district was estimated at 30 million dollars by 1975 (Clark 1970:28).

In 1893, at the height of the boom, the only business directory of Angels Camp produced since 1855 was published. In addition to the merchants, businessmen, teamsters, livery stable operators, saloon keepers, and others, discussed below in the section on Commerce and Industry, most of those listed were involved in mining-related activities. These included mine owners, superintendents, managers, engineers, bookkeepers, hoistmen, millmen, blacksmiths, carpenters, millwrights, machinists, laborers, and the ubiquitous miners, by far the greatest proportion of occupations listed that year (Calaveras County 1893:518-534). The advent of the Sierra Railroad in 1902 allowed the mills to ship their ore to Selby in the San Francisco Bay Area for smelting, a much more efficient means of transportation than previously available, and increased their income.

When visited by the State Mineralogist in 1914, the Utica mine was described as including nine claims: Utica, Stickles, Rasberry, Brown, Washington, Dead Horse, Jackson, Confidence, and Little Nugget, all located on the Dead Horse lead, showing an average width of 60 feet of ore. Work was opened up through two vertical shafts, with the Cross shaft the main working passage. The mill had 60 stamps, weighing 1000 pounds per stamp, dropping 7 inches at 104 drops per minute and crushing 5 tons per stamp through punched screen; pulp was concentrated on thirty-six Frue vanners. The mill was driven by a 150 h.p. motor, furnished with power by the Union Water Company, which was controlled by the Utica Mining Company.

The Gold Cliff mine, another one of the Utica Company’s group of mines, lay west of Angels Camp and included the Pilot Knob, Gold Cliff, Madison, Specimen, Fairfax, Excelsior, Peachy, No. 1 and No. 2 Placer Claim, located on a western spur of the Mother Lode vein. The mine was being operated from the 1500, 1600, 1700, and 1800-foot levels, with ore hoisted from the incline shaft in 4-ton skips by a 225 h.p. double drum hoist. Ore was trammed from the shaft by electric traction to the mill which was supplied with a Blake crusher, 50 stamps, and twenty-four Frue vanners. The Utica Gold Mining Company was owned by the Hayward, Hobart and Lane Estates, with headquarters in San Francisco, and employed 155 men at the Utica and 96 at the Gold Cliff (Hamilton 1915:81-82, 111-112).

Other mines noted in and around Angels Camp included the Angels mine, located on Angels Hill, consisting of six patented claims and one placer claim: Billings, Crystal, Oneida, Dr. Hill, McCormick, Angels, and the Beda Blood placer claim. The property was operated through a three-compartment shaft, 850 feet deep, and the Crystal shaft, 600 feet deep. The mill operated with 40 stamps, weighing 850 pounds each, ore was concentrated on sixteen 4-foot Frue vanners, and then sent to the Selby Smelting Works. Power was provided by the Pacific Gas & Electric Company, and the Angels company employed 70 men. The Lightner mine, a fractional claim adjoining the Utica and Angels mines, had been sunk to a depth of 900 feet, with ore processed in a 60-stamp mill. The Sultana, located north of the Angels mine, had a vertical shaft of 700 feet deep, sunk on vein, and was processed in a 20-stamp mill, but had been idle since 1905 (Hamilton 1915:68-69, 89-90, 108).

During the early 20th century, Angels Camp, along with the rest of the gold regions in California, experienced sporadic mining activity until World War I, when most of the mines closed, never to reopen, and were sold for scrap metal. On the western fringes, the Gold Cliff Mine struggled on for a few more years, as did the smaller family-operated mines in the area. Only the Carson Hill Gold Mining Company provided steady employment until it, too, closed during World War II, when virtually all mines in the area were shut down by the United States Government as non-essential war-related industries under Executive Order L-208.

Only prospecting and development continued after the war, and Angels Camp remained at a development plateau for many years, with only a few modern additions to mark economic improvements. In the 1980s a brief resurgence in mining at the Carson Hill Mine and the Royal Mountain King mine (at Salt Spring Valley) provided some steady income, but both have since shut down.

The early preeminence of mining, however, ensured that all other local industries would be its auxiliaries. Transportation, lumbering, water, power generation, and ranching have all been directed and influenced by the mining industry.

By Judith Marvin, 2011

Study from: Historic Resources Inventory and Evaluations, Historic Commercial Center, Angels Camp, Calaveras County, California. Prepared for Planning Director, Angels Camp, By Judith Marvin and Terry Brejla, Foothill Resources, Ltd. April 2011.

References

Borthwick, J.D., 1948 3 Years in California. Index and Foreword by Joseph A. Sullivan. Biobooks, Oakland, California.

Buckbee, Edna Bryan, 1932 Pioneer Days of Angels Camp. Calaveras Californian, Angels Camp.

2005 Calaveras County Gold Rush Stories. Edited by Wallace Motloch. Calaveras County Historical Society, San Andreas.

Carson, James H., Edited by Peter Browning, 1991 Bright Gem of the Western Seas, California 1846-1852. Great West Books, Lafayette, California.

Clark, William B., 1970 Gold Districts of California. Bulletin 193. California Division of Mines and Geology, San Francisco.

Elliott, Wallace W., 1885 Calaveras County, Illustrated and Described. W.W. Elliott, Oakland, California. Reprinted 1976 by the Calaveras County Historical Society, San Andreas.

Gudde, Erwin G., 1969 California Place Names. The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographic Names. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Hamilton, Fletcher, 1915 Mines and Mineral Resources of Amador County, Calaveras County, Tuolumne County. California State Mining Bureau, San Francisco.

Limbaugh, Ronald H., and Willard P. Fuller, Jr., 2003 Calaveras Gold, The Impact of Mining on a Mother Lode County. University of Nevada Press, Reno and Las Vegas.

Long, Earnest, editor, 1976 Trips to the Mines, Calaveras County 1857-1859. Calaveras Heritage Council, San Andreas.

Noyes, Leonard Withington, 1858 Journal and Letters, 1853-1858. Unpublished Manuscript on file, Essex Institute, Salem, Massachusetts.

Taylor, Bayard, Foreword by Joseph A. Sullivan (1859), 1951 New Pictures from California. Biobooks, Oakland.

Wood, R. Coke

1952 Murphys, Queen of the Sierra. Oldtimer's Museum, Murphys.

1955 Calaveras, the Land of Skulls. Mother Lode Press, Sonora.