The French of Lost City

Most of the information on the Frenchmen of the Stone Houses has been gleaned from an article written by Donald Barrows in 1959 and in 1961 published in Las Calaveras, the quarterly bulletin of the Calaveras County Historical Society. Researching the archival records and newspaper accounts, Mr. Barrows uncovered the history of the property, the subject of his master’s thesis. [see sidebar for full article].

Ten stone buildings, including a two-story house, another two-story building, and several cabins and sheds, were located on the land patented by Barbe and Marion Eubank. Why Barbe constructed some of his buildings on the Eubank parcel is unknown, but possibly he wasn't aware of the property lines.

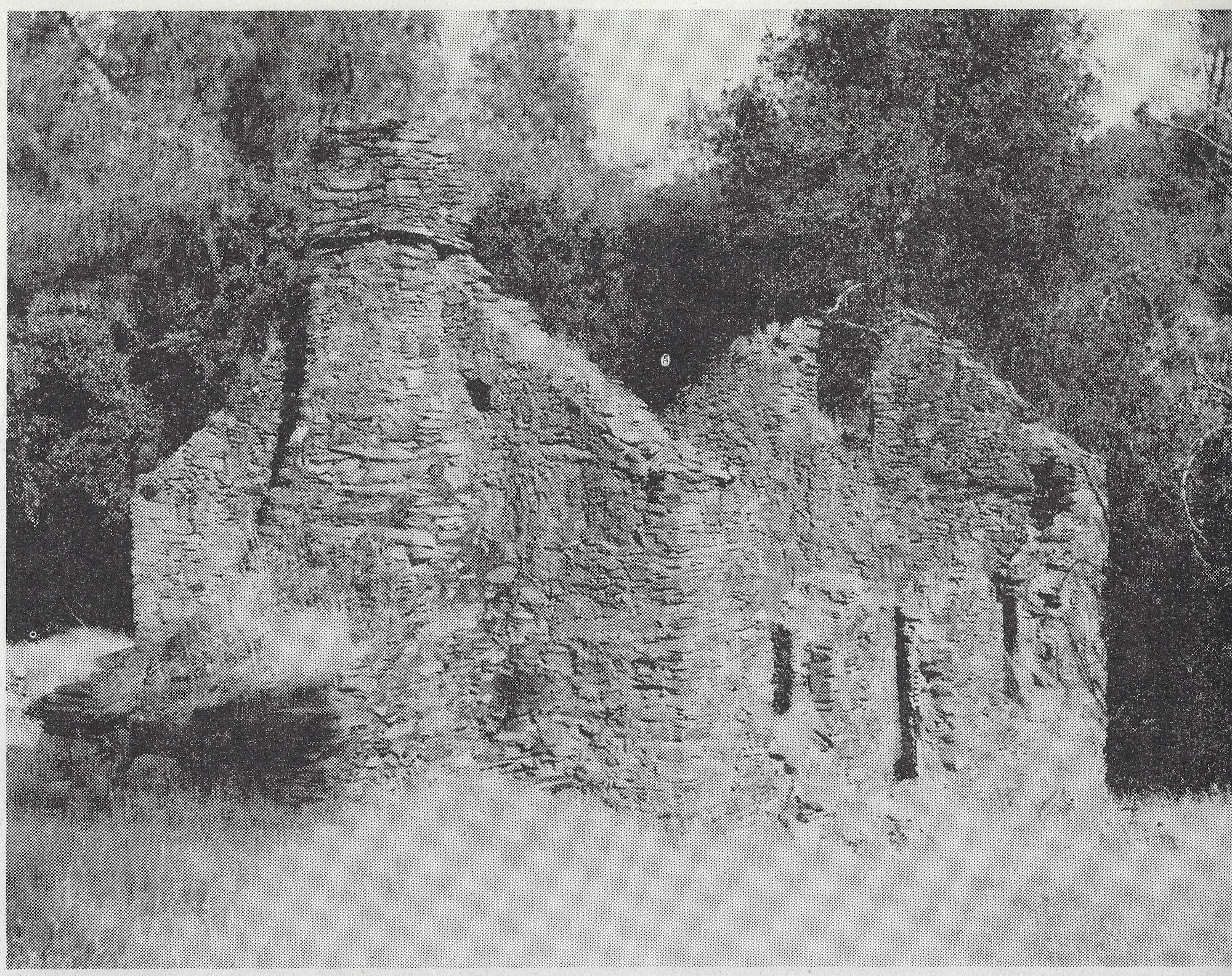

Barbe resided at the Stone Houses with five or six other Frenchmen, men who lived there at various times and performed diverse jobs. Informants remembered Barbe and the others constructing the stone buildings during the late 1870s, utilizing the schist which was dug from their mine (claimed in September 1879 as the Stone House mine) just east of the main house. They found some placer gold, as well as some quartz gold, and the excavated flat rocks made excellent building material. In constructing the walls of the buildings, two rows of rock were placed together, with the flat edges out, and mud mortar was placed between them, creating a thick battened wall.

One interesting aspect of the two-story stone house is the stone bread-baking oven in the rear of the fireplace. According to Julia Costello, who has conducted extensive investigations of the stone ovens of Calaveras County, they are much like those to be found in French Canada, with a beaver shape, in contrast to the beehive shaped ovens of the Italians and Mexicans. Bread was baked using the following method: a fire was started in the oven the door closed, and when the wood had burned down to hot coals the coals were swept out, the bread placed inside, and the door again closed, baking the bread for the requisite amount of time.

The Frenchmen at the Stone Houses raised cows, horses, sheep, goats, chickens, and ducks, as well as fruit and vegetables. The stone walls for animal pens and for garden retaining walls abound. The men were evidently very industrious, especially Barabe, constructing the many buildings, a slate road which extended north along the creek to the old Valley Springs road, and mining in their shaft and along the stream drainages.

Informants also remembered long sluice boxes running continuously during the wet season. They were placed on rock walls west of, and across the creek from, the stone houses. A stone arrastra, with drag stones nearby, is situated on the east bank of the creek, near a stone-lined well.

Although there are numerous bedrock mortars within and adjacent to the site, there is no evidence of any Native Americans residing there during the occupation of the Frenchmen. These bedrock mortars are to be found throughout Salt Spring Valley along most of its drainages.

Nor is there any evidence of women in residence. The Frenchmen evidently did all of the work themselves, growing produce, raising stock, and selling their produce in the nearby towns of Milton and Copperopolis and at the numerous farms in the area. It was on one of his vending trips that Barbe was killed in Copperopolis, on June 2, l895. He stopped to water his stock at the roadhouse of Eli Moore, when the horses ran away with the wagon, crushing him beneath.

A few of the Frenchmen stayed behind to tend the gardens, and local rancher William Dean was paid by the estate to care for the property until May 1896, but it was evidently abandoned thereafter. The land was sold by the State, Barbe apparently having no heirs, but subsequently two sisters were found in France and the remainder of the estate was distributed to them.

Besides Barbe, the man who resided longest at the Stone Houses was Amon Legrant, who worked for Barbe. After Barbe's death he moved a mile south, to a cabin on the Pedroli place. He remained there for the rest of his life, cared for by the Hunt family after they purchased the ranch.

Although there have been accounts that the Frenchmen wore military uniforms and were escapees from the army of Maximillian in Mexico, there is no evidence to substantiate that story. As Barbe was living and working at Alban Hettick's Ranch in 1870, and was naturalized locally in 1873, he was evidently another of the body of French-Swiss immigrants to the region. The men who worked for him were probably also involved in this serial migration, settling in the valley and working for a countryman for a period of time until they obtained enough money to purchase or homestead their own land, or to move on to another area.

Today the Stone Houses lie in ruins, their roofs of pine shakes burned in a fire which rushed through the area in 1914. Beset by weather, vandals, pothunters, and time, the buildings remain the only legacy of this s mall colony of Frenchmen who settled on Bear Creek, a colony that was the last bastion of the French in Salt Spring Valley.

Judith Marvin, 1996